[ WERSJA POLSKA ]

Dear Readers,

Year 2011 was a year of protests organized in the name of “people’s power”. Demonstrations sweeping through North Africa, Europe, the United States, and at the end of the year Russia, dominated the media. On “Foreign Policy’s” annual list of top 100 Global Thinkers the first 10 places were awarded to “Arab revolutionaries” and „TIME” magazine recognized “The Protester” as the “Person of the Year”. In other media it was often claimed that 2011 brought the biggest advance of democracy since 1989. Although the protests were held in extremely diverse places they were all considered to be closely interrelated.

But have we really just experienced the next “wave of democratization”? If so, what has it left ashore and what has it taken with it? Should democratic activists congratulate themselves on the events of the past 12 months?

In today’s “Liberal Culture” we pose these questions to people daily preoccupied with the theory and practice of democratization. The issue consists of three interviews and a summarizing commentary. In the first interview Susan Buck-Morss, professor of philosophy at the City University of New York, presents her views on the condition of contemporary capitalism, its relationship to democracy and the possibilities of change created by the protests known as Occupy Wall Street movement. Our second interviewee is a Serbian democracy activist, Srdja Popovic. Over the past 15 years, Popovic was involved in preparing numerous – though not always successful – non-violent democratic protests in countries all over the world. In our discussion he speaks, among others, on how to plan a revolution and explains how he ended up on the “Foreign Policy’s” list as “an Arab revolutionary”. In the last conversation we talk to Carl Gershman, a longtime president of the National Endowment for Democracy, one of the most important democracy promoting institutions, annually spending tens of millions of dollars on this purpose. From the interview we learn how is this money spent, who donates it and what results it brings. A commentary by “Liberal Culture’s” contributor Joanna Kusiak summarizes some of the issues discussed and raises an extremely important question – How to end the revolutions started in 2011?

In today’s “Liberal Culture” we pose these questions to people daily preoccupied with the theory and practice of democratization. The issue consists of three interviews and a summarizing commentary. In the first interview Susan Buck-Morss, professor of philosophy at the City University of New York, presents her views on the condition of contemporary capitalism, its relationship to democracy and the possibilities of change created by the protests known as Occupy Wall Street movement. Our second interviewee is a Serbian democracy activist, Srdja Popovic. Over the past 15 years, Popovic was involved in preparing numerous – though not always successful – non-violent democratic protests in countries all over the world. In our discussion he speaks, among others, on how to plan a revolution and explains how he ended up on the “Foreign Policy’s” list as “an Arab revolutionary”. In the last conversation we talk to Carl Gershman, a longtime president of the National Endowment for Democracy, one of the most important democracy promoting institutions, annually spending tens of millions of dollars on this purpose. From the interview we learn how is this money spent, who donates it and what results it brings. A commentary by “Liberal Culture’s” contributor Joanna Kusiak summarizes some of the issues discussed and raises an extremely important question – How to end the revolutions started in 2011?

Enjoy the reading!

Editorial Team

1. SUSAN BUCK-MORSS: Sometimes to progress means to stop, to pull the emergency brake

2. SRDJA POPOVIC: Revolutionaries without borders

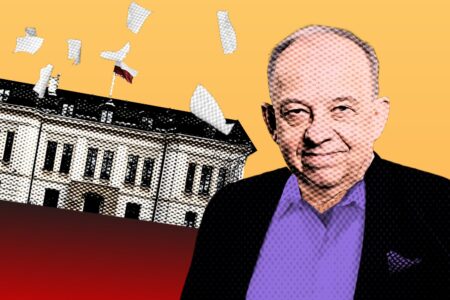

3. CARL GERSHMAN: Democracy as a learning process

4. JOANNA KUSIAK: Decapitating a many-headed Hydra: how to finish a revolution?

Susan Buck-Morss interviewed by Joanna Kusiak

Sometimes to progress means to stop, to pull the emergency brake

Joanna Kusiak: You’re a politically engaged philosopher. You’ve signed a letter of support for Occupy Wall Street and CUNY’s student protests, you talk about OWS during your philosophical seminar and at the same time you claim there is no political ontology. Why?

Susan Buck-Morss: My prejudice against ontology comes from reading Adorno and his virulent criticism of existential ontology as he sees it so powerfully expressed in Heidegger, but then leading to such disastrous political consequences: the impotence of his philosophy vis-à-vis fascism, if not its actual collaboration. By resolving the question of Being before subsequent political analyses, the latter have no philosophical traction. They are subsumed under the ontological a priori that itself remains indifferent to their content.

JK: What does it mean in terms of political action?

SBM: If you start from a claim of ontological position, everything has to follow from it. It doesn’t matter if you choose your ontology because of who you are (some identity politics) or if you begin with something like “All history is the history of class struggle” (which is an ontological principle, for example, Antonio Negri holds on to) – you fundamentally know the answer to anything, before you even start. The only criterion left for accuracy is internal consistency. I think it is true not only for leftist identity, but also for Anarch-ism vs. Marx-ism, vs. any other -ism. There may be times when anarchist politics is absolutely called for, but not because I have decided that ‘I am an anarchist’, not because anarchism is my principle, but because that is a powerful move right now. In order to do politics that way, you’ve got to make judgments every particular time, you cannot deduce anything from first principles.

JK: This reminds me of my favorite Walter Benjamin’s quotation. In one of his letters to Gershom Scholem, concerning political action, he says that in politics you have to act ‘always radically, never consistently’.

SBM: It’s absolutely true. Every time you have to allow for the possibility that you may be wrong and start thinking anew again and again. Then you have to pay attention to what’s going on. You can’t presume ‘Oh, it’s capitalism’ or ‘Oh, it’s neoliberalism’. It’s particularly important now, because some real shift is going on, a shift maybe bigger than the one which occurred in 1989.

JK: Why?

SBM: Because it’s not just a geopolitical shift, there is a real questioning of all the fundamental categories with which we’re dealing – literally all of them. Nation state, democracy, national identity (or any kind of political identity), solidarity, equality – all of these principles seemed to be synonymous with modernity and we actually shared them both in Marxist and in bourgeois science. But all of them are somehow not adequate any more. I haven’t seen such thing in my lifetime before.

JK: So there is no capital-ism now, just capital?

SBM: That’s not quite what I mean. Marx didn’t use the word capitalism very often. Rather, he wrote a book called simply “Capital”. It’s Werner Sombart who introduced the word capitalism in the late 19th century and I think by that time it had become a belief system.

* Susan Buck-Morss is an American philosopher and intellectual historian, Professor in Political Science Department at City University of New York. Her most recent book, ”Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History” (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009), offers a fundamental reinterpretation of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic by linking it to the influence of the Haitian Revolution.

** Joanna Kusiak, sociologist and urban/political activist from Warsaw (Poland), Fulbright Advanced Research Fellow at City University of New York. She is writing a dissertation about urban revolution in Warsaw at the University of Warsaw and Darmstadt University of Technology. Lives between Warsaw, Berlin and New York.

***

Srdja Popovic interviewed by Łukasz Pawłowski

Revolutionaries without borders

Łukasz Pawłowski: A few weeks ago “Foreign Policy” magazine published its annual list of 100 Top Global Thinkers. 10 first positions were granted ex aequo to “Arab revolutionaries”. The striking thing is that among them there are two non-Arabs – you and Gene Sharp – retired professor of political science from Boston. Can you explain how you – a Serbian biologist – ended up listed as an “Arab revolutionary”?

Srdja Popovic: Well, back at the end of the 1990’s I was a revolutionary in Serbia. In 1997 with a group of fellow students we established an organization called “Otpor” – in Serbian meaning “Ressistance” – which aim was to topple the dictatorship of Slobodan Milosevic. In October 2000, using only non-violent means of political struggle, we finally succeeded. Thousands of Serbs took to the streets of Belgrade thus preventing Milosevic from forging the results of presidential elections and forcing him to resign. After that for a brief time I served as a Serbian MP but in 2003 I gave up my political career. With friends, Andrej Milivojevic and Slobodan Djinovic, we founded CANVAS – Centre for Applied Non-Violent Action and Strategies – and since then we have been devoted to spreading the experience we gained in opposing Milosevic all around the world. Because we organized workshops for people engaged later on in the Arab Spring and because we wrote a pretty popular non-violent struggle manual called “Non-Violent Struggle: 50 Crucial Points” – translated by now into 6 different languages and read by revolutionaries across the Middle East and Iran – “Foreign Policy” connected the dots and put us in the context of those events. We always repeat that it is the people actually doing the revolution who deserve all the credit for what is achieved. Yet, I believe we have a small role of passing to them the knowledge that is useful in their undertakings.

ŁP: And what about Gene Sharp? He is 83 years old now so I assume he was not so actively involved in the Arab Spring as you were…

SP: Sharp is a brilliant scholar who spent most of his life researching the phenomenon of non-violent struggle against dictatorships. His most popular book, “From dictatorship to democracy: A conceptual framework for liberation” has been translated into 28 languages and used by revolutionaries throughout the world, including us in Serbia at the time of “Otpor”.

ŁP: How did “Otpor” come across the ideas of Gene Sharp?

SP: In May 2000 at a conference in Budapest I met Bob Helvey, retired U.S. army colonel who became a close associate of Sharp and a devoted promoter of his ideas. Gene’s work helped us structure what we had already been doing in Serbia for a few years. Up to that point we learned all the strategies of non-violent resistance simply by doing them. Suddenly we bumped into a man who had been studying this approach for over 30 years. By reading his books we learned that many of our techniques of fighting Milosevic’s regime were in fact invented many years ago and thousands miles away.

* Srdja Popovic, one of the organizers of the Serbian nonviolent resistance group “Otpor” which in the years 1997-2000 lead a successful non-violent campaign against Slobodan Milosevic’s regime. In 2003, Popovic and other ex-Otpor! activists established Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS). Throughout the years they worked with democratic activists from over 40 countries including Georgia in 2003 and Ukraine in 2004. Recently CANVAS has worked with the April 6th Movement – one of the key groups behind the Egyptian nonviolent uprising – as well as with other democratic movements in the Middle East.

** Łukasz Pawłowski, a PhD candidate at the Institute of Sociology, University of Warsaw; visiting scholar at the Department of Political Science, Indiana University; member of the editorial team of “Kultura Liberalna”.

***

Carl Gershman interviewed by Łukasz Pawłowski

Democracy as a learning process

Łukasz Pawłowski: The National Endowment for Democracy has an annual budget of almost 140 million dollars. How big does it make it among other democracy promoting institutions?

Carl Gershman: Although we are an independent and private institution, our budget comes primarily from an annual appropriation made by the U.S. Congress. Compared to the amount of money United States spends on democracy promotion through such agencies as the USAID and the State Department, the NED budget is not that large. It represents about 5 or 6 percent of the total amount spent by the U.S. on democracy assistance. There are also other public and private institutions like George Soros’ Open Society Institute that is rather large as well. The NED is thus only one of a number of players. The European Union also spends a great deal of money on democracy promotion and is actively considering the creation of an institution parallel to our own, called European Endowment for Democracy. This is a Polish initiative, by the way.

ŁP: What means of support do you usually provide for countries you are assisting? For example in what ways were you involved in the Arab countries during the Arab Spring?

CG: Obviously you should not start getting involved only during “the spring.” You have to be present during “the winter” as well. We were very active in supporting many groups in Egypt and other Arab countries: independent labor unions, election monitors, nongovernmental organizations advancing women rights or protecting human rights in general, and especially independent media and groups using new communications technologies. In the countries that were relatively open like Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, and Yemen, we were able to do more than we could in closed societies like Libya, Tunisia, or Syria. But we were even able to be active in these dictatorships, supporting some human rights organizations and groups working from exile. You cannot just enter when things open up – you have to be there before that. That’s certainly the way it was in Central Europe in the 1980s when the NED got started. We didn’t wait for Solidarity and other independent groups to succeed. We supported them when they were underground organizations.

ŁP: In what particular activities do you engage?

CG: There are three forms of help we can offer. One is grant support to NGOs. Second is training and technical assistance, largely provided by NED’s four core institutes, which are international democracy support organizations associated with the Democratic and Republican Parties, the AFL-CIO, and the Chamber of Commerce. They provide aid to their counterparts abroad, whether it is organizing political parties, training election monitors, helping parliaments o develop their committee structures and oversight procedures, helping business associations develop and promote more open and transparent economic processes, helping workers organize – all those things are done under this second category of training and technical assistance. The third aspect, which is especially important in dictatorial countries, is what I would call moral support and solidarity for people who must operate in very difficult situations. These people often face arrest, and of course their lives are threatened as well.

ŁP: What do you mean by “moral support”?

CG: We defend human rights, we help give people in closed societies political recognition and visibility, we put out alerts when they are in trouble, we let them know that they are not alone. Václav Havel, who just passed away, did a great deal of work providing what I have called moral and political solidarity with dissidents in danger – the very same solidarity he received from the West during communist times.

[ continue reading... ]

* Carl Gershman is an American intellectual and democratic activist. From 1981-1984 he was Senior Counselor to the United States Representative to the United Nations. Since 1984 he has been the President of the National Endowment for Democracy.

** Łukasz Pawłowski, a PhD candidate at the Institute of Sociology, University of Warsaw; visiting scholar at the Department of Political Science, Indiana University; member of the editorial team of “Kultura Liberalna”.

***

Decapitating a many-headed Hydra: how to finish a revolution?

A call for papers was recently announced by Harvard University with a slick question as the topic for the conference: “How to finish a revolution?” This question is posed at the end of a year in which many unfinished revolutions took place: mass protests, occupations, and rallies, turning one after another into media events. 2011 unfolded according to seasons of protests: the Arab Spring was followed by a European Summer (which honestly should not be limited to Europe—recall the protests in Chile) and the American “occupying” Fall. For a moment it seemed that winter would cool down the protesters’ zeal when, for many quite unexpectedly, demonstrators appeared on the streets of a city where the biting cold makes not the slightest impression on anyone: Moscow. Although it is too early to tell, we may have just entered the Russian Winter. The problem is that all these protests seem to end just like the seasons do—they pass. While for years it was believed that in countries such as Egypt and Libya protests could never occur because of state repression (or in the U.S. because of individualism and consumerism), 2011 can be called a year of newly launched but uncompleted revolutions. Seeing that currents events have provided an answer to the question “How to start a revolution?,” reasonable and pragmatic Harvard scholars have posed a new question: How to finish a revolution?

Finding answers to questions (political as well as scientific), is an essential element of the construct known in the West by the proud name of “knowledge society”. According to the old philosophical logic, the difference between knowledge and wisdom is that knowledge consists in a set of responses (which more or less popular sophists were always ready to deliver), while wisdom (represented by Socrates) is the ability to pose really good questions. A really good philosophical question can be recognized by the fact that regardless of whether or not we can give an answer to it, it fundamentally changes the way we look at the answers that have already been given. The knowledge society is not necessarily a wisdom society and it might in fact be quite a foolish one. Contemporary educational systems as well as the media shape the political debate in a way that promotes answers similar to those give on TV quiz shows: fast, witty and in line with the existing rules of the game.

The most serious accusation against Spanish “indignados” and American “occupiers” was their refusal to provide concrete answers. The protesters concentrated on questioning, which is probably the most philosophical part of political activism, and by doing so radically changed the language of public debate. The most interesting intellectual activity in all the seasons of 2011 was to observe how certain issues, concepts, ideas, and events moved from the domain of mere political speculation to the realm of ordinary conversation at the kitchen table and in subway stations. And yet, after a hundred days of the occupation and several thousand arrests, after many hours of general meetings and full days of discussions and, finally, after numerous police actions evicting occupation camps from public spaces of American cities, the mood among occupiers is like the mood on a still ship: we are in the middle of a lake, nobody wants to paddle back to the shore but the wind has somehow stopped blowing in the sails. Not only does nobody know the answers, but we do not seem even to know how to begin responding to the revolutionary question, “What is to be done?”.

Actually, there are a number of tempting replies, but none of them seem plausible or even thinkable within the limits of existing system, and so we think them quietly, knowing that there is less reason in them than imagination (and imagination was never highly prized in the knowledge society, so that we who imagine are a bit ashamed). Get rid of Wall Street? Cancel all public debts? Eliminate credit rating agencies and financial markets? Put bankers on trial? Introduce a guaranteed income everywhere? Dispose of all politicians and replace them by lottery? Most of potential responses either fall into the category of political fiction (like during the Cold War it was a political fiction to imagine the Eastern bloc collapsing), or else are completely unsatisfactory. The fantastic character of the first lies in the fact that there is no group and no state with the power to implement them, while incompleteness of the latter in the fact that implementing them in one country would be simply quixotic. For example, though many people readily agree that the enormous power of credit rating agencies is illegitimate and extremely harmful, no government has the courage to publicly announce that it will disregard their demands and not make any further painful cuts. The huge disappointment with Obama was caused by the fact that his “Yes, we can” turned out to be limited only to what was allowed by Wall Street financiers and global capitalist networks. While history knows stories of the successful decapitation of tyrants and dictators, the decapitation of a many-headed Hydra still remains in the domain of mythology.

In the absence of meaningful answers, it would be easy to ignore the newly instigated revolutions if it wasn’t for their unique coincidence in time—after years without protests they keep erupting one after another in totally unexpected places and even if they are populist, they’re not xenophobic: the universal dimension of challenges we face is highlighted and rather than “outsiders” (e.g. immigrants) the system itself is blamed. If, as Susan Buck-Morss claims, the essence of political thinking lies in being able to capture novelty in a world where we think that everything has already happened, the question concerning the end of the revolution seems to be premature or simply ill-posed, because it refers to the perspective of particular revolutionary events rather than their universal significance. If the question of “How to finish a revolution?” is to be truly revolutionary, the most appropriate answer should be “Do not finish, but properly start”. It’s easy enough to imagine a history book from the future in which the year 2011 figures as the beginning of the beginning, and the end only coming twenty or fifty years later. If the global system requires a new, global kind of revolution, the question about the end must be replaced by the question of the beginning: how particular protests may contribute to building global solidarity and how to synchronize the revolutionary timeline; how to feed the revolutionary fire during many coming seasons in which—hopefully—more revolutions will be started.

The answer may lie in combining the various strategies of action presented in the interviews published in today’s “Liberal Culture”: the strategy of the philosopher and that of an activist. When asking great questions about what seems impossible today, we should also do everything possible to legitimize them by everyday actions, small but arduous struggles for the well-being of particular individuals and societies. So instead of New Year’s resolutions for 2012 I propose a political-philosophical exercise: on December 31st think with all the power of your imagination on the one thing that you would like to change in your city, in the political system, or in your politics (even if it seems impossible) and then tell ten people about it. Five of them will probably not believe it but together with the other five try to do three things which with a little bit of effort can be accomplished and which will make that first great thing just a tiny little bit more possible.

** Joanna Kusiak, sociologist and urban/political activist from Warsaw (Poland), Fulbright Advanced Research Fellow at City University of New York. She is writing a dissertation about urban revolution in Warsaw at the University of Warsaw and Darmstadt University of Technology. Lives between Warsaw, Berlin and New York.

***

Concept: Łukasz Pawłowski

Cooperation: Joanna Kusiak, Ewa Serzysko

Illustrator: Wojciech Tubaja

Kultura Liberalna nr 155 (52/2011), December 27th 2011