[ Wersja polska / polnische Version / Polish version ]

[ Wersja niemiecka / deutsche Version / German version ]

Ladies and Gentlemen!

Already in the 1970s, the Polish United Workers Party leadership dreamed of energy might. In the era of General Jaruzelski’s junta, the construction of a nuclear power plant at Żarnowiec was started. Lately, again we’ve been hearing of returning to ideas from the Communist era. Meanwhile, new phenomena emerge around us – ones that we can hardly understand if we merely draw on the past.

European integration based on economy, politics, a revolution of European citizens and a common cultural memory founded on the critical assessment of both totalitarianisms – all this has been debated many times, but integration through energy? Now that is something new!

And yet here we are witnessing the birth of a new era. The inevitable depletion of resources, of coal and oil, on which the industrial aged and the modern global economy were constructed, is discussed across Europe. Meanwhile, scientists continually remind us of humanity’s role in the progressing climate change.

Let us look at Germany: already under the SPD-Greens coalition of 1998-2005 the decision had been taken for a gradual transformation of the energy sector, on nuclear phase-out and the increase of the share of renewable energy sources (RES) in electricity generation. The Fukushima meltdown accelerated that process. After over a decade since it was initiated and almost two years after it switched to turbo-gear, the German energy turnaround, known as the Energiewende, seems not only feasible, but most of all – very inspiring. Issues seemingly addressing the hermetic realm of technology are becoming the talk of town, in the media, at cafesand homes all across the nation, from Kiel to Constance. The Germans turned their energy transformation into a project comparable with sending a man to the Moon.

In many European countries, however, that “new industrial revolution” causes much anxiety. In Poland it is rather depicted as an irrational if not – insane plan for de-industrialization and perhaps even economic suicide. No wonder: Energiewende’s success would question many of our country’s policies, particularly the unnerving bravado of the Polish government’s nuclear project, already difficult to justify from an economic and environmental point of view.

Renewable energy is being developed in Poland too; however, it seems to grow somewhat parallel and even contrary to state policy. The decisions of Donald Tusk’s government are turning more and more surprising and seem to growingly go against the values that the ruling coalition declares to hold dear. Although the ritual flogging of the government with critique has now become something of a fad, in this case one really needs to take the questions deeper. Why are we seeing the work on a provisionary piece of legislation known as the “small energy three-pack”, while the draft RES Act has been postponed once again? The draft contains, among others, German-inspired solutions which would allow individual citizens to turn into “prosumers” – that is at the same time consumers of energy from the grid, and producers of energy owning small and micro renewable installations (e.g. solar). Why was this project, liberal in its spirit, and allowing for the implementation of the ideals of a de-centralized and “democratic” energy production – thrashed?

The German expert in energy economics, Claudia Kemfert, in an interview opening today’s issue, puts forth a powerful thesis: we have forty years of struggle over electricity ahead of us. What does that mean? Kemfert sees the Federal Republic’s resignation from nuclear energy in favor of renewables as the key issue in contemporary politics – and perceives it in moral terms and through responsibility for civilization. But what should we make of the growing share of coal power plants in Germany (meaning: a step back into the former era)? See for yourselves.

We asked two experts Wojciech Jakóbik i Grzegorz Wiśniewski about the Government’s policy. It would be difficult to imagine two accounts as divergent as the ones we got. Jakóbik picks the German energy transformation to pieces. The Federal Republic has betrayed the ideals of a bottom-up transition for the benefit of the citizens and instead is implementing a top-down transformation, he argues. He also defends Poland’s energy policy, explaining why he sees it as rational and aiming at independence.

Grzegorz Wiśniewski, however, points out the four million “civic” renewable installations in Germany. Poland, according to him, is not going in the direction of its neighbor, because the breakthrough in energy is held back by various lobbies. Such as energy companies – and although they should be implementing the state’s energy policy, in reality the state is realizing the interests of the energy business – he asserts. Furthermore, he shows why he believes that the parting of ways between Germany and Poland in the energy sector might be in the long run harmful for the latter.

Jakub Patočka too writes of government-business relations that are far from ideal, as he presents the “Švejk style Energiewende, meaning the ongoing corruption scandal over RES development in the Czech Republic. In the realm of energy policy, writes Patočka, an Iron Curtain is still cutting Europe in half, and it is about time we decided which side we want to be on.

* * *

This Topic of the Week is another one in the series prepared together by the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation and “Kultura Liberalna” within the framework of the Polish-German project on the future of the European Union.

The issues published thus far: “Should Germany sacrifice itself for the EU?” with texts by Ivan Krastev, Clyde Prestowitz, Karolina Wigura and Gertrud Höhler; “Europe is a club of humiliated empires”, the only interview with Peter Sloterdijk in the Polish press in years; as well as “The Dream of the Welfare State” with texts by Wolfgang Streeck, Richard Sennett, Jacek Saryusz-Wolski and Łukasz Pawłowski. More issues coming soon!

Enjoy your reading!

Kacper Szulecki

1. CLAUDIA KEMFERT: A battle over electricity

2. WOJCIECH JAKÓBIK: Energiewende consumer – a slave

3. GRZEGORZ WIŚNIEWSKI: Energy revolution and counter-revolution

4. JAKUB PATOČKA: Energy revolution, Švejk-style

A battle over electricity

Claudia Kemfert talks to Kacper Szulecki about the German energy turnaround

Kacper Szulecki: You recently published a book under the powerful title “The fight for electricity” – Already in the first chapter you quote the thesis that the German energy transformation, or Energiewende, is not achievable by 2022. That is the date that the Merkel government has set for the phase-out of the last nuclear plant. Is that too much of an ambitious plan?

Claudia Kemfert: The Energiewende is more than just the nuclear phase out. We have four decades of radical energy policy change ahead of us, but the direction has to be decided now. The opponents of energy transformation argue that it is not achievable in this relatively short period, that the nuclear phase out will cause electricity supply shortages. However, by 2022, when the last seven nuclear power plants in Germany will be shut down, there will be enough renewable energy and power from coal and gas to replace nuclear. Nobody expects the final transition to renewable energy by then. For that we have time until 2050.

What does the German society think about that?

Germans want to phase out nuclear energy and to increase the share of renewables, however, nowadays; the public acceptance of the Energiewende appears to be dwindling. Skepticism and fear are increasing, stoked by various myths: for example that the Energiewende is too costly, or that it is bad for the German economy. These myths prey upon many peoples’ fears of shifting from the established order to a new one. Take for example the often repeated thesis that energy prices in Germany are going up just because of the energy turnaround, and that the Energiewende is terribly expensive. In reality there are many factors influencing the rising prices. But the Energiewende opponents place it all squarely on the incentives stipulated in the Renewable Energy Act (EEG).

And so is it not true that the Energiewende is costly?

Energy in general is costly. Skeptics claim that 100 billion euro will be spent on renewable energy support, which seems like a lot. But you have to know that Germany buys 90 billion euro worth of fossil fuels each year. That puts the Energiewende in a realistic perspective. In fact, the cost of renewable energy is rather relatively small for the average household, about 1 percent of consumption expenditures. The cost of electricity is between 3 and 5 percent. That is several times less than we spend on mobility or heating. At the same time, RES are causing the reduction of wholesale electricity prices. Big industry is benefitting from that, it buys ever cheaper energy on the market. Fossil fuel prices are constantly rising – and they will keep rising. In the long run, RES are cheaper than fossil fuels. Germans are thus making a smart investment for the future.

What about the accusations that the investment is carried out without the consent of the key stakeholders – the citizens?

The claim that the Energiewende is an example of a planned economy and has replaced the forces of the free market is yet another myth based on an understatement. As if the past energy market was free! Nuclear energy and fossil fuels have long been subsidized but the consumer never sees it tacked onto their energy bill the way it is with renewables. That as other myths – are simply not true. Behind these arguments there are concrete economic interests of different entities. It’s a heterogeneous group including some of the utilities, companies with coal-powered plants, energy-intensive industries that fear high investments in energy efficiency and conservative ideologues who think that everything “green” is bad.

What do you think will be the result of the energy transformation for the future of Germany?

* Claudia Kemfert – professor of economics, she heads the Energy, Transportation and Environment department at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW). She is also Professor of Energy Economics and Sustainability at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin.

** Kacper Szulecki – political scientist and sociologist, Dahrendorf Postdoctoral Fellow at the Hertie School of Governance and guest researcher at the Dept. of Climate Policy of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW).

***

Wojciech Jakóbik

Energiewende consumer – a slave

Initially, in the 1980s, the goal of implementing the Energiewende was the transformation of the German energy consumers into prosumers. Independent energy producers were to cater for themselves and sell the surplus to the public network. The need for becoming independent from the depleting and ever more expensive fossil fuels was being emphasized, along with the energy empowerment of the German citizens. Today those ideals have been completely betrayed in Germany.

Today, the Energiewende is being implemented from the top down, through a centrally planned program of subsidies, while disregarding the will of German energy consumers, who pay the highest bills in Europe, right after the Danes. The minister of the environment of the Federal Republic, Peter Altmeier, suggested, that by 2040 the costs of Energiewende can reach even a trillion euros. Environmental groups like for example the non-governmental organization Agora Energiewende, are looking for solutions to reduce the costs of the energy revolution, but more and more attention is paid to mega-scale projects like DESERTEC in the Sahara desert.

Foreign reactors paid for by the public’s money

The energy turnaround’s plan has also been criticized by the EU energy commissioner Guenther Oettinger. He claims that the final phase out of nuclear energy by 2022 will lead to a situation where Germans will still be using nuclear energy – however produced with reactors which are situated outside the Federal borders. Since the passing of the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG), the sums on energy bills have been rising faster than the inflation rate. What is more, since the plan was announced, the use of coal in Germany rose by 4.9 percent. And so, phasing out nuclear energy, means Germans are opting for the cheap coal alongside RES. Furthermore, the German Energy Agency points out, that for accomplishing Energiewende’s goals, there will be several dozen gas and coal plants needed in the country. Fossil fuel powered plants are to be an alternative during the periodic interruptions in RES supply, which can happen with a sudden change in weather. Electricity imports are another alternative.

Critics of the energy turnaround emphasize, that because of the support schemes, its burden is being mostly carried by the general citizenry. Prosumer ideals remain unrealized, contrary to the interests of particular lobbies, like the producers of solar panels and wind turbines. It is worth noting that the turnaround is also supported by the European Commission, promoting the intervention on the carbon-dioxide emissions allowance market (Emission Trading Scheme – ETS), called backloading. The bureaucrats from Brussels decided that the allowances are too cheap, and therefor do not create an incentive to depart from “dirty” fossil fuels. That is why they want to artificially raise their price, temporarily removing some allowances from the market. The goal of that deeply non-market move is the increase of costs in conventional energy sources to a level high enough to make RES more competitive in relation to the former. The Eurocrats face a tough challenge, because backloading has been opposed already by the energy intensive industry lobby as well as Poland and a majority of the members of the European Parliament. The Germans are divided on the issue. The theme is supposed to be back on the agenda of the Commission though.

A centrally steered Energiewende has no link to the idea of dispersed energy, based on RES and installed in a bottom-up manner by prosumer-volunteers. Today the consumers are indeed the slaves of Energiewende. It is precisely the pricey projects, like the German energy turnaround, that diminish the competitiveness of Europe in relation to the emerging powers, like China. This is linked to the phenomenon of the so called carbon leakage – the flight of heavy industry beyond the borders of the over-regulated Old Continent. A signal of change can be seen in the trade battle between the EU and China, whose cheap solar panels are a serious challenge to the German RES sector seeking to defend its market share in Europe. It is possible that the low-cost installations from China will allow Europeans for an independent energy turnaround in their homes.

The Polish match for energy sovereignty

The current environmental minister, Marcin Korolec, took far reaching steps to provide a rational answer to the EU’s climate policy. Thanks to his efforts, the November climate summit of the UN will take place in Warsaw. It will allow the Poles to play in the match for the future of climate policy at their home pitch. Korolec is skeptical of setting higher climate targets. Poland is trying to reach the now binding target – three times 20 percent by 2020. The EU decided to reduce CO2 emissions by 20 percent, increase the share of RES in the energy mix to 20 percent, and increase energy efficiency by 20 percent by that date. It moved well in the direction of achieving these goals. We have doubled our GDP over the past two decades, at the same time reducing emissions by almost 30 percent. Korolec warns against the premature adoption of the so called milestones, through which the European Commission wants to impose even more ambitious long-term plans. He wants the EU to hold its decision until the global negotiations are completed, which is anticipated to take place in 2015. Most likely, he is assuming that in the course of these negotiations the economic calculus will get the upper hand on ideology, and there will be no “new Kyoto”.

Poland must emphasize innovation in the energy sector. We need to support our scientists, researching innovative solutions. It would be good if the development of the RES sector underwent a gradual deregulation and if the rules became as simple as possible. Poland cannot afford another social program like the German Energiewende and it cannot afford a stricter climate regime. If the environmentalists are criticizing the expensive subsidies in the mining sector, its time they noticed the critics of subsidizing RES. Renewable energy should develop from the bottom-up, according to prosumer ideals. Especially, since the answer to the controversy over the need for a climate policy and a state-controlled energy sector will have a crucial importance for the competiveness of the industry in Poland and Europe in the years to come.

* Wojciech Jakóbik, expert at the Jagiellonian Institute. He deals with energy and security

** Translated from Polish by Kacper Szulecki.

***

Grzegorz Wiśniewski

Energy revolution and counter-revolution

Poland does not seek an understanding and dialogue with Germany on energy policy, does not want to use the neighbor’s experience, and does not seek compromise.

For two decades now, Germany has been steadily aiming for a shift in economic paradigms, moving towards an energy sector that is sustainable both environmentally and technologically. Poland in turn is developing its energy supply in an ever starker opposition to Germany, petrifying the existing, growingly outdated model typical for the 19th century, based on a “central coal plant” or its nuclear substitute. The latter is a model of energy policy that was state of the art in mid-20th century. This situation introduces a growing dissonance in the generally good neighborly relations between the two counties.

Poland’s opposition to the German energy policy has been increasing since 2008, when after the political green light for the “3×20” Climate Package, the EU was shaping the directives on the emissions trading scheme, “clean coal” technology, renewables and the means of achieving energy efficiency targets. At that time, the German government was already implementing its 2006 strategy, according to which by 2022 all nuclear plants were to be phased out and substituted – even outgrown – by renewable energy sources (RES). In the difficult negotiation process of late 2008, over the final shape of the energy and climate directives, Poland was looking for support not to its Western neighbor, but to the new member states and to France, which empowered the coal power sector and became an impulse for the rash decision to begin such nuclear programs. It also meant that despite the strong EU support for RES the implementation of the renewables directive ended up at the far end of the Polish government’s priority list. That mode of thinking was then in 2009 inscribed into the official strategic paper “Poland’s energy policy until 2030”, sealing the programmatic divergences between Poland and Germany.

Romantic Germans, pragmatic Poles?

The Fukushima meltdown confirmed the direction of Germany’s energy policy, and deepened the divergences. The final decision of the German ruling coalition on the complete phase out of nuclear energy before 2023 was presented in Poland as the effect of an irrational emotional surge after the tsunami, due to which “the greens pushed the (romantic?) Germans against nuclear energy” (as for example Konrad Szymański, MEP, would have it). Ironically, the air of pragmatism is in these circumstances continuously given to the statements of the national energy companies, that although the German breakthrough is an idea detached from economic realities, it is beneficial for Poland because… it paves the way for the export of electricity from Polish coal plants to Germany.

Nobody wants to see that what is happening is exactly the opposite – Germany has a surplus of energy that it is exporting. Along with a number of other EU member states (e.g. Great Britain), implementing the Climate Package boasts a wide investment program in the RES sector. There are 25-30 GW of new capacity being installed across the EU annually, and a great majority of that capacity is the RES. The price of energy from renewables is becoming lower than that from fossil fuels, and that process can neither be stopped nor reversed. Meanwhile, the opportunistic approach to the Climate Package in Poland has resulted in the lack of any significant new capacity development, not even for substituting the old coal plants. Poland will face an energy deficit already in 2015-2016. Unfortunately, the programmatic skepticism towards the Energiewende, including the underestimation of the nation’s potential in renewable energy will lead to the need for importing energy from, among others, Germany, and this can feed a wave of new “conspiracy theories” and irrational decisions on future energy policy.

Energy lobby in place of the state

Not noticing and downplaying the role of RES, or even blocking their development, the example of which is the nearly three-year-long delay in the implementation of the EU directive, maintains an “open door” for nuclear energy and unverified solutions in the energy sector, such as shale gas or CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage). In the face of these mechanisms, the situation is difficult for the so-called independent green energy producers as well as for foreign energy sector investors, who are operating in a very different reality outside of Poland. The Polish utilities, without a clear signal for change on the part of the government, are not making up the technological and structural distance vis-à-vis the EU.

On the other hand, in the apparent lack of other major market players, the national energy companies are becoming the key recipient of energy policy, the illusionary depositaries of the nation’s energy security. Influential lobbies, linked to the energy companies, blend with the public administration. Steering the course of policy and regulation year after year, they keep drawing Poland away from an energy breakthroughand make even the evolutionary changes difficult. It seems that it is not the energy companies who implement the state’s energy policy, but rather conversely – the state pursues the interests of the companies.

Poland and Germany at energy crossroads

As an effect of these policy differences, the energy systems of Poland and Germany vary significantly, especially when it comes to RES. The installed capacity of renewables in Germany is almost two times larger than the entire installed capacity of the Polish energy sector, and the share of RES in the German system (over 41 percent) is almost five times that of our country’s. In spite of that, the German grid operators fully manage to balance the significant production from instable sources (such as wind and solar), while their Polish counterparts have already convinced the government of the alleged threat to energy security occurring even with such low shares of wind and solar energy.

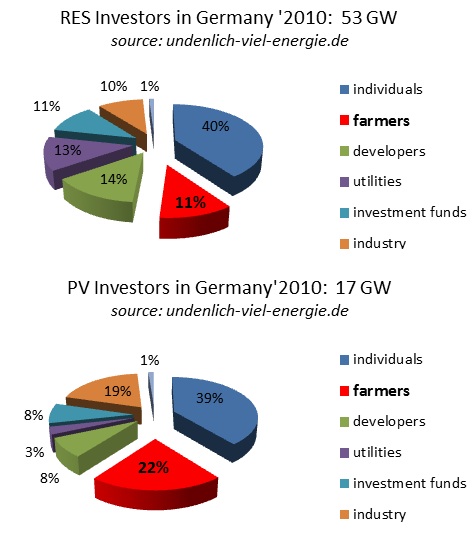

Even starker differences occur in the RES ownership structure, especially in the currently most dynamic segment – prosumer energy. In Germany already in 2010 there were some 4 million producers of electricity from RES. A majority of these had small installations (average capacity of ca. 20 kW). The figure illustrates the structure of German investors in the entire RES sector and, as an example, in photovoltaic (producing electricity from solar energy – ed.)

Overall structure of RES investors (over 4 million installations) and in photovoltaic (PV) in Germany in 20120. Source: Undenlich-viel-energie, own elaboration IEO.

As one can see, some 11 percent of all RES investors (share of the total installed capacity) are farmers, and in the photovoltaic (PV) sector, their share is as high as 22 percent. The farmers alone have invested over 14 billion euro in PV. Individuals and households are the major RES developers in Germany (ca. 40 percent share of the total capacity), while the traditional utilities have only 13 percent, and in the PV segment – a mere 3 percent of installed capacity.

Compared to the Western states, the Polish situation on small installations looks very different. In 2012 there were 1043 energy producers in the segment of fewer than 5 MW installations. As a rule, they were owned by independent developers. The share of that segment in the overall renewable energy production was, however, only at ca. 15 percent. The twenty largest RES producers all belonged to the four national energy companies and supplied over 70 percent of the entire green energy, which clearly differentiates the Polish renewable energy market from the more developed markets in other countries. In the segment of micro-installations, less than 50 kW, only a minuscule number (257) were connected to the grid.

Without prosumers there will be no revolution

Germany’s energy policy is supported by the millions of citizens producing green energy or working in the green industry. Political and regulatory blocking of RES development, especially of micro-installations, prevents the creation of a prosumer sector and this lack makes the necessary changes in the Polish energy sector difficult which leads to the petrification of its archaic structure. The absence of perspectives for the national RES market impedes the expansion of the industry producing components for renewables, because of which Poland loses a major pillar in the development of the so called “green economy”.

Poland, justly emphasizing both security and competitiveness in energy policy (though unnecessarily negating climate protection goals), in practice, without a societal, dispersed renewable energy sector, worsens its situation in both of these areas. The almost programmatic split between the Polish and the German energy policy is not good for Poland and at the same time does not help Germany in the accomplishment of the difficult, but vital breakthrough.

* Grzegorz Wiśniewski – president of the Renewable Energy Institute (IEO) in Warsaw

** Translated from Polish by Kacper Szulecki.

***

Jakub Patočka

Energy revolution, Švejk-style

Make no mistake, we will not let the pesky Germans spoil us with their solar sorcery. And if you want to know the culprit, look no further than the Sun.

When it comes to renewable energy policy, one can essentially find two approaches in Europe. First, we have the countries that are eager or even zealous in promoting an energy policy U-turn. The Germans, above all, have actually managed to turn their Energiewende into their greatest intellectual and industrial adventure of today, a sort of “putting the man on the moon” for the onset of the green era.

Second, we have the countries that view this tendency with skepticism, or at least reluctance. When you look at a map of Europe depicting trends towards adopting renewable energy as an essential part of the national energy mix, it might strike you that here, the Iron Curtain remains intact. As if the approach to renewable energy was a reflection on the general state of the political culture.

Tunneling? It’s the Sun!

Perhaps nothing confirms this suspicion better than the special case of the Czech Republic. Here, the nation’s political and economic elite have managed to pull off a quite subtle and truly devilish trick. On the one hand, a state supported incentives scheme promoted as a “German style endorsement of renewables” was mismanaged in such a way as to pass absurd sums of money to the members of the industrial and political power elite who had privileged access to the incentives.

Yet on the other hand, the scheme’s downfall, caused by the public frustration over this elite making huge fortunes on the high state-guaranteed prices, was spin doctored into a failure of renewables. Hence people perceive renewable, and especially solar, energy itself as the cause of all the losses, rather than the people in political and economic structures that mismanaged and deliberately misused the scheme. Moreover the public have been convinced that they pay for the scheme in their energy bills. Although it has been proven that it represents only a minor share of the rate increases imposed by the Czech power utility, the people have been misled to blame the Sun.

Most likely this was not premeditated. But once the lavishly corrupt Czech power elite saw the chance to suck yet more money from the public budget, they just could not resist. Later, they realized that the robbery had become too large and the public too angry—and they needed a scapegoat. Since those profiting most from the solar bonanza have no interest in any sort of green agenda—actually quite the contrary in most cases—this served them as a scapegoat just perfectly.

One step forward, three steps back

So here we have Energiewende, Švejk style. If you ask the average Czech citizen who stole the money intended to promote renewables, he would—with his infectious smile—undoubtedly point his finger at the Sun.

But this is only step one. The Czech version of Energiewende actually has also a step two, which brings things deliciously full circle. If the public has been convinced—with the blatant assistance of the egregiously incompetent Czech media—that renewables present no future for us, what is the future, then?

You guessed it. As if to demonstrate their shock at the money sucked out of the renewables promotion schemes, the government is seriously contemplating giving price guarantees to fund the construction of the third and fourth blocks of the Temelin nuclear power plant. And this would be 20 billion euros, by far the largest investment in Czech history.

Moreover, structurally it is to be handled like the renewables program. While the fixed prices for sale to the grid in the case of solar energy were guaranteed for 15 years, in the case of the nuclear it is to be an incredible 40 years, which would literally lock in energy policy for two generations. One can ask why anyone would do something so obviously insane. Well, ten years of virtually unopposed nuclear propaganda have created in the majority of Czechs a sort of national nuclear pride. If you are looking for definitive proof of how irrational national self-esteem can be, look no further.

Naturally the project’s ultimate point is to create yet another huge siphon to funnel public money into the jaws of Czech political corruption. Money is after all the oil that keeps the member parties of the current Czech right wing coalition running without friction. Which is not to say that substantial parts of the left wing opposition love it any less.

A dubious nuclear progress (within the bounds of law)

This is set up to happen in a situation where international debate on a future for nuclear energy is as good as dead. We do not need to talk safety, waste, and ethics when it becomes self-evident that a technology has become too unwieldy and obsolete. Nuclear energy today feels like a steam locomotive at the dawn of the diesel era. But… the Czechs do have tradition here. At the start of the LCD era, the state gave large incentives to the multinational Philips to build a factory to manufacture CRTs.

Because nuclear is promoted as a source of both power and national pride, and ours is a nation of irony, it should come as no suprise that the critical public debate is: should Americans build it, or Russians? Make no mistake, we will not let the pesky Germans spoil us with their solar sorcery. And if you want to know the culprit, look no further than the Sun.

* Jakub Patočka – journalist and activist, editor-in-chief of the Czech „Referendum” daily.

***

* Author of the issue’s concept: Kacper Szulecki.

** Collaboration: Jakub Krzeski.

*** Coordination of the project on the side of „Kultura Liberalna”: Ewa Serzysko.

**** Coordination on the part of the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation: Monika Różalska.

***** English editing: Patrick Kozakiewicz.

****** Illustrations: Przemysław Gast.

„Kultura Liberalna” nr 229 (22/2013) May 28th 2013.

This Topic of the Week is another one in the series prepared together by the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation and “Kultura Liberalna” within the framework of the Polish-German project on the future of the European Union.